A ’near-futurist‘ scours data for hidden clues about how the world works

By Mark Mobley for Microsoft Storylab

Photos by Brian Smale

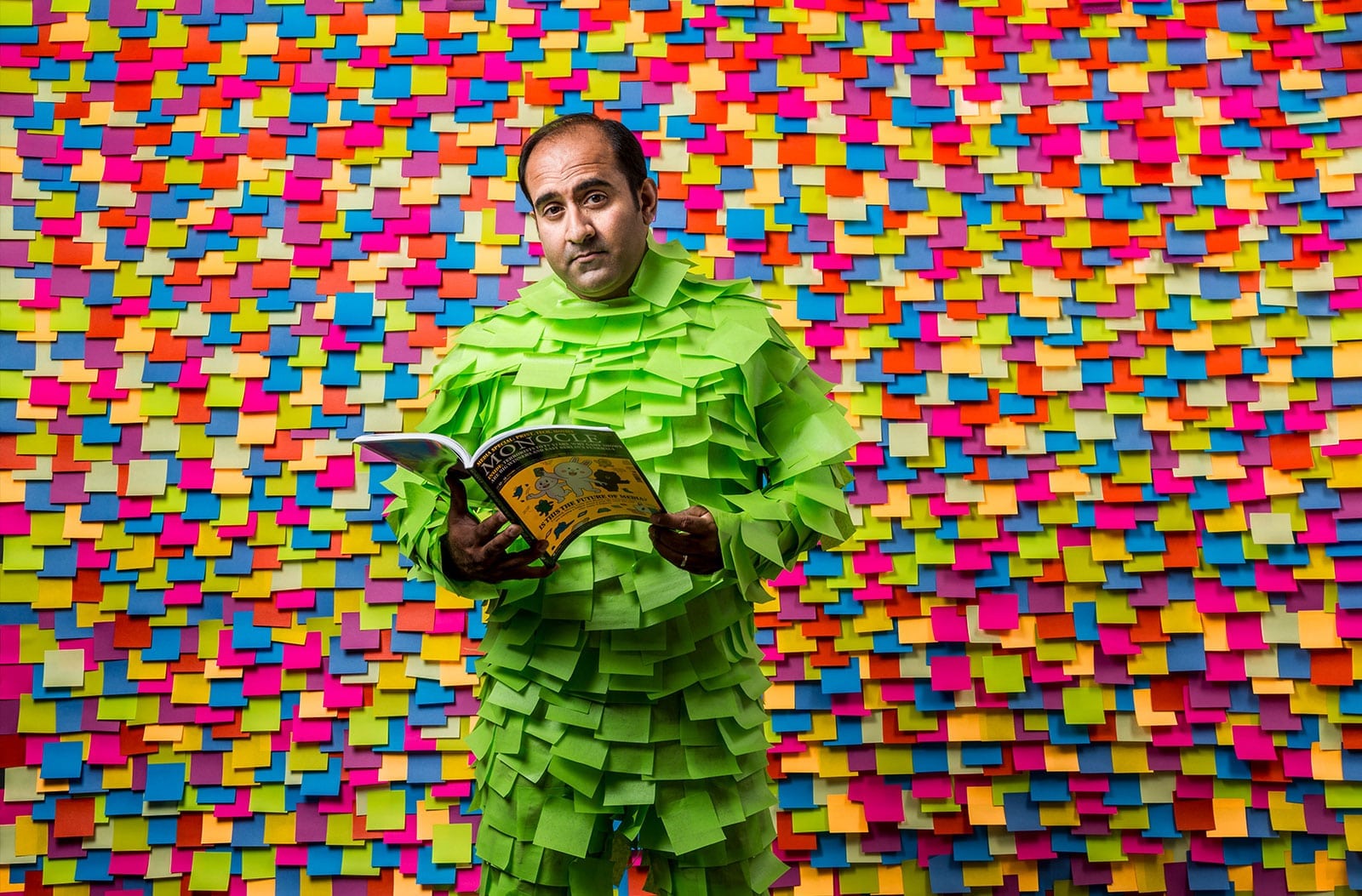

How does self-described “Trend Curator” Rohit Bhargava navigate the future? By shredding magazines and planting sticky notes. Throughout each travel-packed year of international speaking and teaching, he collects untold piles of periodicals, then skims, tears and screens their editorial and advertising content for clues to what’s now, what’s new and — most of all — what’s going to be influential in the years to come.

“The trends,” Bhargava said, “really explain how the world works.”

Using what he calls his “haystack method,” Bhargava sorts and sifts and shifts the material he and his team have found. Gradually, connections are made, combinations arise, synchronicities emerge and trends appear. He compiles what he gleans in an annual series of books called “Non Obvious: How To Predict Trends And Win The Future,” which have been published in more than a dozen languages. These have schooled more than a million businesspeople and interested civilians about the cultural currents, jet streams and eddies that shape our lives.

“You’ve got to look somewhere other than where everyone else is looking,” said Bhargava at his airy home, where visitors are welcomed by photo collages of his two young sons, in a leafy suburb of Washington, D.C. “I tend to pick up a lot of stuff about things I otherwise would never have picked up because the media here are so U.S.-centric.”

His omnivorous media diet includes everything from legacy magazines like The Atlantic and Variety to city magazines (Washingtonian), alumni magazines (Emory magazine), specialty publications (USA Philatelic, Adweek), foreign in-flight magazines and periodicals definitely not published with him in mind (Teen Vogue, Modern Farmer).

The irony of a “near-futurist” relying so heavily on paper in the digital age is not lost on him.

The irony of a ‘near-futurist’ relying so heavily on paper in the digital age is not lost on him.

“I think that people are more surprised about that than I am,” Bhargava said. “What you see is the paper. What you don’t see is my Feedly account, where I read hundreds of stories each week.” He also relies on conversations at conferences and interviews by his associates. But Bhargava sees a certain tactical advantage in scanning a vast amount of information in physical form.

“There’s a reason every James Bond villain looks down on that diorama of the world they’re trying to conquer,” he says. “Hopefully I’m not doing that for evil.”

He smiled and added, “Maybe there is some evil, because I want people to think for themselves and a lot of people don’t want that.”

Bhargava was born in India and came to the United States at 6 months old. After studies at Emory University he moved to Australia in 1998 and began his career at a company called Dimension Data, where he worked for three years before joining the Sydney office of advertising agency Leo Burnett. He returned to the U.S. in 2003 and started working the following year in Washington at Ogilvy. He stayed at that advertising agency until 2012, when he left to start his own consultancy.

Conference and convention planners appreciate the experiences Bhargava himself provides — he speaks at upward of 50 events a year, in addition to consulting with individual companies and teaching smaller groups. “My goal is to give them something they can do, not just inspire them,” he said. He wants to help his audiences find interesting ideas in unexpected places.

While he may appreciate tradition and rigorous methodology, he is anything but a stickler for doing things the way they’ve always been done.

“Our habits are really hard to unlearn,” he told an audience at a recent construction software convention in San Antonio. “The things that we know, the best practices, are really hard to abandon.

If we are going to be innovators, we are going to have to leave some things behind.

“If we are going to be innovators, we are going to have to leave some things behind.”

That’s why one of his five rules for Non-Obvious thinking is to “be fickle” — in other words, keep it moving. The others are “be observant,” “be curious,” “be thoughtful” and “be elegant.” That final command is the guide for the pithy names he likes to assign to the trends he observes.

For example, ”brand stand” is his term for how corporations can make themselves more attractive by backing up their work with socially conscious messaging and actions. (“The job of marketing is not to sell a car, it’s to get people to come into the dealership,” Bhargava explained.) “Predictive protection” is what he calls device makers working to anticipate and defend user vulnerabilities. And “approachable luxury” is the idea that experiences and objects that evoke authenticity and sincerity are now sometimes considered as valuable as high-end products from legacy makers.

In addition to isolating 15 trends for each edition of the Non Obvious books, he also looks back at previous years to reassess the accuracy of his own predictions. Take two from 2013: ”precious print” and “branded inspiration.” While consumers’ fondness for books and print media in general hasn’t waned (Bhargava still gives that trend an A five years later), brands are less willing to stage dramatic one-off events to stand out (today he gives that one a C).

While reevaluating trends, Bhargava realized he could also present them in new ways. He is increasingly using data visualization as a storytelling tool. The Microsoft Power BI platform allowed him to create The Non-Obvious Trend Experience, a periodic table of elements-style dashboard that shows how trends connect across years, industries and areas of interest.

The playful, informative Power BI dashboard is yet another product of an ever-expanding Non-Obvious universe. He's planning what he calls "the most Non-Obvious thing to do," a short-form podcast about the past hosted by a futurist. And he and his wife, Chhavi, are co-owners of the publishing imprint Ideapress, which has published 22 books and has another 12 coming soon. His own contribution to the series will be a volume on running a small business.

"I think any of us can be more innovative, more creative," he told his San Antonio audience. "We just have to give ourselves permission to do it." He demonstrated that the following morning by leading a workshop of about two dozen executives and staffers. They gathered around tables piled high with magazines.

He opened with a drawing exercise and soon the group was on to Bhargava's haystack method, scouring the magazines before them for new ideas and things they hadn't seen before. "I know it's uncomfortable for some of you, but these magazines are for ripping," he said. "I want to hear you ripping things out of these magazines. It might be an ad, it might be a story. Feel free to collaborate with your table."

Curation is the ultimate method for transforming noise into meaning.

Two tables pulled the same story about new leashes for walking with children. Another person landed on a makeup line from Crayola. Yet another found an under-the-desk bicycle apparatus that generates power through pedaling. "That's like next-level LEED certification," Bhargava joked. "You can power your own building."

In under an hour, the participants caught a glimpse of what is for Bhargava a year-round process producing mounds of material that gain more meaning with age and comparison.

"Sometimes we have to give ourselves a little bit of time," he said. He thinks of his haystack method as akin to collecting frequent flyer miles. The ideas are there, mounting over time, ready be cashed in when they're needed.

Frank Di Lorenzo Jr., a participant from Sacramento, California, called the session "excellent."

"It got me to think a little more creatively," Di Lorenzo said. "It's like taking a step. If I always start on my right foot, this was my left. For an hour, he accomplished a lot."

"I never saw anybody present this kind of topic before,” added Mary Cunningham of Jupiter, Florida. “It helps you think beyond the obvious. Don't take things at face value. It allows you to open your mind to other ideas. The way he presents the material, it's very easy to comprehend and allows the ideas to sink in easily."

"Curation," as Bhargava writes in “Non Obvious” and shared in his seminar, "is the ultimate method for transforming noise into meaning."

Even if the noise is as much the shredding of magazines and riffling of sticky notes as it is the rising, roaring tide of cultural chatter.