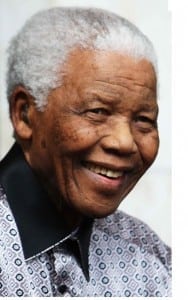

A few years ago when I traveled to South Africa, I first realized the awesome power that Mandela held over his country and wrote about it in a post about the challenges of “leaderless revolutions” and why the world needs leaders like Mandela . Since then, his story and work have been a continual source of inspiration for me. Whenever I get that tired interview question of the famous person I’d most like to meet, he’s usually at the top of the list.

Last night as I walked along the street near Leicester Square in London, I saw a movie premiere event in front of one of the largest movie theaters in the city. Though I couldn’t see what it was, all the signs above the theater were for the new Mandela movie. Then I returned to my hotel, saw the news that he passed away – and I have been thinking about him all day. Last year I wrote about his story in Likeonomics – and though I’ve shared it before on my blog, I thought it would be fitting to republish it today.

Not only because he changed the world around him, but because he happened to do it with a generosity and likeability that few other politicians seem capable of today. I know I have never seen him speak in person, or spent enough time in South Africa to really understand his legacy. But perhaps the biggest sign of his impact lies in this surprising reaction from people like me, and how powerfully we already miss him.

Nelson Mandela Excerpt From Likeonomics:

If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.

—Nelson Mandela

The first time I experienced the powerful influence of Nelson Mandela was from the front seat of a taxi cab riding down the streets of Jo’burg (as the locals call Johannesburg). Mandela’s picture was on billboards along the highway to the city even though he was no longer president of South Africa, and my driver was speaking about his influence and how he had inspired the nation. That story started nearly 20 years ago.

In 1993, tens of thousands of Afrikaners (white South Africans) were preparing for war. Three years earlier, a man named Nelson Mandela had been released after 27 years in prison. He was no hero to this group. They saw him as the founder of a terrorist organization who threatened their way of life and belonged in jail. They were ready to fight.

As reporter and biographer John Carlin wrote, that was the moment where Mandela began ‘‘the most unlikely exercise in political seduction ever undertaken.’’1 He invited the Afrikaners leaders over for tea and listened to their concerns. Then, he persuaded them to abandon their guns and violence. The battle never happened.

A year later, he was sworn in as president of South Africa and vowed to make reconciling the racial tension between whites and blacks his number-one priority. Somehow he had to overcome decades of hate and convince people ready to die for their causes to see one another as brothers. In one of his first acts as president,Mandela invited Francois Pienaar, the captain of the South Africa national rugby team (Springboks), to have tea with him. That afternoon he struck an alliance, asking Pienaar to help him turn rugby into a force for uniting all South Africans.

During the Rugby World Cup in 1995, Pienaars led the mostly white players of the Springbok team in singing an old song of black resistance, which was now the new national anthem, ‘‘Nkosi Sikelele Afrika’’ (‘‘God Bless Africa’’). It was a powerful demonstration that the players believed in having a united South Africa. Inspired, the team fought the odds and made it to the finals against New Zealand.

On June 24, 1995, minutes before the final match would start, Mandela went on the field in the middle of the stadium wearing his Springbok green shirt to wish Pienaar and the team good luck. The crowd, made up of mostly white South Africans, was stunned. For many years, that green shirt had been seen as a symbol of only white South Africa. For a black man to wear it was unheard of.

The crowd erupted in cheers of ‘‘Nel-son, Nel-son’’ and everyone across South Africa celebrated. Mandela would go on to lead the racial reconciliation both during his presidency, and then after as an ambassador to the world for South Africa. In 2004, the country was awarded the world’s largest stage to host the 2010 FIFA World Cup. It is now seen as a likely future Olympic destination, as well.

This story of South Africa’s triumph was chronicled by Carlin in his book Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and the Game That Made a Nation. It was so powerful, it inspired the Academy Award–winning film Invictus by director Clint Eastwood.

Why People Believe in Likeability (and Why They Don’t)

The fate of South Africa is linked to the story of one man’s personal charm and likeability. This may seem like an extreme example. After all, not many people have the gift that Mandela has. Yet, his experience does explain the very fundamental role that likeability can take in inspiring belief and changing our world around us. People didn’t follow Mandela because of the ideas; they followed because of him. When he invited you over for tea and listened to your concerns, and then spoke, you couldn’t help trusting his vision.

WE RECENTLY REMOVED COMMENTING - LEARN WHY HERE >